摘要写作练习来源文章

Explicit and Implicit Approaches in Foreign Language Teaching

1. Introduction

A key issue in language learning and teaching is whether language learning should be treated as an intellectual, systematic and conscious task or as an intuitive, unconscious activity. (Stern, 1983: 403; Stern, 1992:327) Though a clear distinction between explicit and implicit ways of learning and teaching did not begin until the mid-1960s, the option between the two approaches can trace back to a long time ago. For example, the traditional grammar-translation approach is a typical explicit approach to language teaching. (cf. 李银仓:2003) Palmer (1922) distinguished spontaneous (implicit) and studial (explicit) capacities, and Bloomfield (1933) laid importance on relatively low-level cognitive activities in which thinking about language (explicit approach) was less important than acquiring automatic responses, thus laying foundations for the later influential audio-lingualism in 1960s. (cf. Stern, 1992: 328) During the period 1965 to 1970, the behaviouristic interpretation of learning which dominated the audiolingualism was attacked by Chomsky (1959, cf. Stern, 1992:328). Carton’s experiment during this period signaled a shift of emphasis from an implicit to an explicit orientation. Around the same time a series of investigations by a group of Swedish researchers, the GUME Project, focused specifically on the implicit-explicit option. Another important figure, J. B. Carrol, who opened the debate of implicit-explicit option in 1964, closed it in 1971 by arguing that an explicit and an implicit strategy are compatible with one another. During the 1970s, research experience was gathered on language learning in the natural environment, in bilingual situations, and through immersion schooling. In all of these situations a language is not acquired through systematic study but absorbed largely unconsciously through exposure to the language in use. The meaning of “implicit” learning thus gradually shifted from unthinking practice techniques to subconscious absorption of the second language under conditions of spontaneous communication. The argument about the explicit-implicit option in this new guise was taken up in the mid-1970s by Krashen’s Monitor theory and continued into the 1980s. The Monitor theory views language learning as basically an implicit process in which explicit knowledge serves to “monitor”. In 1978, Bialystok (cf. Stern, 1992: 328) developed a model of second language learning including three knowledge resources which she labeled as ‘other knowledge’, ‘explicit knowledge’ and ‘implicit knowledge’. (ibid) This model acknowledges that it is possible to know some things about a language explicitly and others only implicitly. Entering the 1980s, some writers began to advocate a more balanced view. For example, Sharwood Smith (1981, cf. Stern, 1992:328) and Farech et al. (1984) both evolved models that consider the option between explicit and implicit learning not as dichotomous but as a continuum in which the two approaches complement each other.

Development in the study of explicit-implicit learning from psychology is almost parallel to the study of it in language teaching. In 1967, American psychologist A. S. Reber first raised the term ‘implicit learning’. Since then, psychologists began to study the differences and relations between implicit learning and explicit learning. In late 1980s it had become a hot topic for study in psychology. (cf. 郭秀艳,2004; 陶沙,2002) These studies cover all aspects of human cognition, and language learning is one of the most typical items in their studies. The discoveries of these studies provide evidences to studies in language learning and teaching on the one hand and on the other hand offer refutations to some language teaching theories. While this may be true, it seems that linguists seldom keep an eye on the development of studies about the same topic in psychology, so this paper tries to review the development of the same topic in both fields so as to get a better understanding of the issue.

2. A psychological view of explicit learning and implicit learning

Implicit learning refers to the learning process that involves no consciousness or strategy, while explicit learning is a process that is guided by certain strategies or procedures and always involves conscious efforts. (张兴贵,2000;陶沙,2002;郭秀艳,2002) Since Reber raised the concept of implicit learning in 1967, more and more psychologists began to be interested in explicit-implicit option in learning. Studies on this problem expose more about human cognition mechanism and can help people better understand language learning process.

2.1 Differences between explicit learning and implicit learning

The differences between explicit learning and implicit learning are reflected in the following three dimensions: (1) Explicit learning involves conscious learning, while implicit learning is automatic. What’s more, experiments show that in certain circumstances unconscious learning mechanism can better detect subtle and complex relations than conscious learning does. (郭秀艳,2004) (2) Explicit learning is changeable, while implicit learning is stable. Explicit learning can be affected by such factors as age, intelligence, emotion, character, motivation, environment, etc. Contrary to that, implicit learning is stable both in the process and in the result. (3) Explicit learning dwells on the surface structure level, while implicit learning goes into the deep structure level. In a sense it can be said that implicit learning is more abstract than explicit learning. Reber’s experiments in 1976 show that under some special conditions implicit processing of complex materials is better than explicit processing. Other experiments show explicit learning and implicit learning have independent biological mechanism respectively. For example, explicit learning is influenced by the hippocampal & limbic-diencephalic—cholinergic transmitter system, while implicit learning is affected by the basal ganglia & striatum—dopaminergic arousal and activation system; explicit learning activates the right half of human brain while implicit learning activates the left half of human brain which is connected to abstraction. Staldler (1997) argues that implicit learning causes horizontal relationships of information items while explicit learning causes vertical relationships of them. (ibid.)

2.2 Similarities between explicit learning and implicit learning

From 1980s more and more researchers find that explicit learning and implicit learning are not totally independent from each other. Actually the two are correlated. First, both learning approaches depend on such factors like situation, context, stimulating means, etc. Second, both approaches need the involvement of attention, the difference being that implicit learning might involve less attention. (ibid.) 张兴贵(2000) argues that explicit learning is the basic means of cognition to which implicit learning is an auxiliary means. 郭秀艳(2002)proposes that highlighting different alternatives according to different learning materials is necessary for achieving optimal correlation between explicit and implicit learning. Furthermore, in dealing with complex learning tasks there should first be an implicit knowledge as the basis and then an explicit task model can be built for the tasks.

2.3 Interactions between explicit learning and implicit learning

Experiments (Reber, 1976, 1980,1994. cf. 郭秀艳,2004) reveal that when the grammar rules to be learned are too complex for learners to find, simple encouragement will stimulate rule-searching psychology in the learners which blocks implicit learning process in effect; but if the grammar rules are demonstrated with some specific examples by people familiar with them, the explicit guidance will enhance the implicit learning. Experiments also show that when learners use explicit and implicit strategies together they can achieve optimal learning effect. In other words, there is a coordinating effect between explicit and implicit learning. (郭秀艳and 杨治良, 2002) Another experiment done by 郭秀艳et al in 2003 tells that there is actually a trade-off between explicit learning and implicit learning. The trade-off relationship between the two approaches makes them sometimes complement each other and sometimes compete with each other but they tend to reach a balanced state. The experiments with different age groups-old people, middle-aged people, university students, junior middle school students and primary school students show a decrease of unconsciousness but an increase of consciousness in learning from childhood to old age.

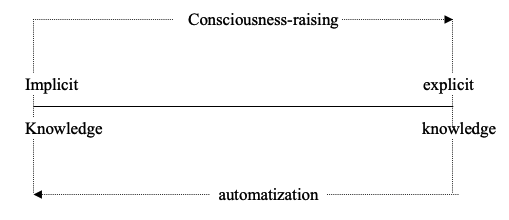

Actually, explicitness and implicitness are not two opposites of a dichotomy. In many cases they are on a continuum where the two move towards each other. Explicit knowledge can be automated and become implicit. Reversely, implicit knowledge can be realized by consciousness and become explicit. (郭秀艳,2003) On this point Faerch et al.’s model of explicit/implicit knowledge can best illustrate the process:

Figure 1 The interrelation between implicit and explicit language learning (Faerch et al. 1984:203)

- A review of the implicit/explicit issue in language pedagogy

3.1. The explicit teaching strategy

Advocates of an explicit teaching strategy assume that second language learning is a cognitive process leading to an explicit knowledge of the language. Such language knowledge includes how the language functions, how it hangs together, what words mean, how meaning is conveyed, and so on. An explicit teaching strategy encourages students to look at learning as an intellectually challenging and worthwhile task. The main point of this strategy is to make the language clear and transparent, to help learners understand the underlying principles, and to give them a sense of order, consistency, coherence, and systematicity about the way the language operates. The techniques employed in this strategy include the following:

Metacognitive counseling techniques. During the course of instruction, teachers deliberately give students advice on how to learn. There might be admonitions, words of encouragement, or specific suggestions on how to respond to error correction, how and when to apply what has been studied, and so on.

Guided cognitive learning techniques. It has the following means:

Observation. Learners are made to be aware of the critical linguistic features by perceiving and observing so as to identify them in texts, and to distinguish them from other features by comparison or contrast. Observation can help learners to familiarize themselves with difficult, subtle, or puzzling but crucial aspects of the language.

Conceptualization. Through conceptualization learners raise what they have perceived to rational knowledge. The process of conceptualization is also the process to hinder or highlight certain language items according to learners’ background, maturity, ability and objectives.

Explanation. An explanation may be presented by the teacher as a general principle which is then exemplified by one or two illustrations and applied through practice in exercises or drills. The rule deducted from the explanation serves not only as a guidepost but also as a reminder or handy mnemonic which can be referred to whenever the particular language problem arises.

Mnemonic devices. The teacher designs some rules or means to help students memorize things better. For example, teachers use rhyming a lot to help students understand and memorize difficult language item.

Rule discovery. The teacher deliberately withholds the explanations to a question so as to stimulate students to discover the underlying principles themselves. The grammar-translation method in the 1800s is a typical example of excessive use of this inductive method.

Relational thinking. This technique makes up for the weakness of much explicit teaching in which one linguistic item is taught in isolation from other language phenomena. The means included in this technique are differentiating, comparison and contrasting.

Trial-and-error. The teacher gets learners to experiment with a new form, word, phrase, or intonation pattern, and to find out how it works and what it conveys to an interlocutor.

Explicit practice. This technique includes repeated observation, exercises, or drills on the basis that learners know the rules underlying the language phenomenon that is being practiced.

Monitor. This technique which evolved from Krahsen’s Monitor Theory calls for a balance between fluency and accuracy. Fluency comes from intuitive, implicit language knowledge while the speaker has to depend on his/her explicit knowledge to monitor the actual language use so as to gain accuracy. According to Krashen, both over-monitoring and under-monitoring should be avoided.

3.2. The implicit teaching strategy

The implicit strategy encourages the learner to approach the new language globally and intuitively rather than through a process of conscious reflection and problem-solving. The people embracing the implicit strategy believe that languages are much too complex to be fully described. Even if the entire rule system could be described, it would be impossible to keep all the rules in mind and to rely on a consciously formulated system for effective learning. Some theorists like Krashen (1982) hold that in authentic contexts languages are acquired at a psychologically ‘deeper’ level. Furthermore, there are always learners who prefer intuitive rather than intellectual learning strategies.

According to Stern (1992), there are mainly three types of implicit learning techniques.

Implicit techniques of audiolingualism. The audiolingual method of language teaching can find its origins in the ‘Army Method’ of American wartime language programs in World War II and was most influential in the 1960s. (Stern, 1983:463) This method views language learning process as one of habituation and conditioning without the intervention of any intellectual analysis. Its intention is to make language learning less of a mental burden and more a matter of relatively effortless and frequent repetition and imitation. In this method listening and speaking are given priority and in the teaching sequence precede reading and writing. The techniques involved are memorization of dialogues, imitative repetition (or mimicry), pattern drills, etc.

Experiential teaching techniques. This method shifts the learners’ attention away from the language altogether and directs it to topics, tasks, activities and substantive content. It aims to build a classroom similar to a natural target language environment, and the classroom is usually subject- or topic-oriented. Through the experiential strategy students are prompted to become language users and participants in social interaction or practical transactions. The strategy has gradually evolved since the mid-1960s with criticism against analytic approaches and later on has been marked by Krashen’s second language acquisition theory and immersion experiments in Canada.

Techniques for creating a state of receptiveness in the mind of the learner. This strategy aims to overcome the deeper psychological resistances to second language learning which are difficult to reach by purely rational approaches. These techniques may include comfortable physical environment, sympathetic attitudes of the teacher, soft music, etc.

- Comments on the studies of explicit-implicit option

Though explicit and implicit approaches have different theoretical basis and employ different techniques respectively, they can complement each other in teaching practice. Many theorists try to combine the two in their study even though they may have preference to one side, for example, Rod Ellis (1994), Krashen (1982), etc. What’s more, many other factors such as learner differences, learning tasks and materials, social factors all need to be taken into consideration in teaching. These factors all influence the strategy choice in language teaching.

4.1. Learner differences.

Learner differences include such factors like age, attitude, language learning aptitude, cognitive style, motivation, personality, etc. (Stern, 1983:360; Ellis, 1994: 541-543) In language teaching the teacher should always take these factors into consideration. For example, Bialystok (1981) and Wenden (1987) both find that learners’ belief on language learning influences strategy choices, i.e. those believing in the importance of explicit learning tend to use cognitive strategies while those emphasizing implicit learning will employ communication strategies more. (cf. Ellis, 1994:541) Young children’s strategies are often simple, while mature learners’ strategies are more complex and sophisticated. Thus implicit strategies are more suitable for young children while for adults explicit strategies are more preferred. The result of the experiments with different age groups mentioned in section 2.3 also offers proof to this. Oxford and Nyikos (1989, cf. Ellis, 1994:542) in a study of students of foreign languages in universities in the United States, found that ‘the degree of expressed motivation was the single most powerful influence on the choice of language learning strategies.’ Highly motivated learners used more strategies relating to formal practice, functional practice, general study, and conversation/input elicitation than poorly motivated learners. As for cognitive style, Stern (1983:374) identifies some basic cognitive characteristics like field dependence/independence, transfer/interference, broad and narrow categorizing. Another classification of cognitive styles contains five pairs of dichotomies, namely, componential-integrative, sequential-casual, active-passive, abstract-specific, analytical-memorial (cf. 李银仓,黄喜玲: 2003) In the five pairs of characteristics the former one of each pair is suitable for explicit teaching while the latter one is suitable for implicit teaching. In language teaching the teacher should always consider the different factors in the students and take different approaches accordingly.

4.2. Differentiation of learning tasks or learning materials.

In language teaching the teacher should also select teaching strategies according to different tasks or materials. For example, in listening and speaking class where communicative competence is the priority, implicit strategy should be the first choice. In other courses such as grammar, writing and lexicon, explicit strategies are more appreciated. Ellis (1994) holds that for the materials with complex content, less variables and salient language points, explicit strategy is more suitable than implicit strategy; while for the materials with loose structure, more variables and vague language points, implicit strategy will be more effective. To teach learners ready to take exams such as TOEFL or CET4/6 the explicit strategy is always the first choice, but if the teacher is to teach a short-period training class ready to go abroad, his/her purpose would be to prepare the learners for basic communication skills and the strategy most suitable for the class would be implicit.

4.3. Situational and social factors.

In language teaching the teacher should also consider the social and situational factors of teaching. Teaching English as a foreign or second language to foreigners in English speaking countries is quite different from teaching English as a foreign or second language in a non-English country. For example, ‘immersion’ method can be exercised in Canada, but in China, implementing the same implicit approach would be very difficult. Even in China, different areas have different social and economic situations and in English teaching these situations would influence the strategy choices. A very typical example of this is Yangshuo, a town of the renowned tourist city—Guilin. As a famous tourist destination, Yangshuo has well-off economy and a lot of foreigners coming and going all the time, consequently the demand of speaking English is high and people are more open-minded than neighboring areas. So generally speaking, taking implicit strategy in English classes in Yangshuo is practical and welcomed. But in the rural areas a few miles away from Yangshuo where the economy is not as developed and English teachers, especially competent English teachers, are few, implicit approaches are very hard to be implemented. Hence in teaching the teacher always needs to lay his/her choice of strategy on the foundation of social and situational factors.

- Conclusion

No language teaching method can be said to be purely explicit or implicit. It’s always a matter of degree. As Faerch’s model shows, the destination of explicit knowledge is to be automated and become implicit. Reversely, implicit knowledge can be raised to consciousness and be explicit. Some topics are more easily managed implicitly, while others are better handled explicitly. Some situations are more suitable for implicit teaching but others are not the same case. Some learners benefit more from implicit learning but others may get more from explicit learning. As Stern (1994:347) points out, ‘The fact that we can make a plausible case for either direction indicates that it would be unwise to be too dogmatic on this issue.’